True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction.

True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction.

Still, it may be possible to adapt da Vinci’s methods to the task of writing great fiction. “But wait, Mr. Poseidon’s Scribe,” (I hear you objecting), “Leonardo was a genius. I wasn’t born a genius.”

It’s been argued before that genius is some combination of luck and time spent at an activity. You can’t do much about the luck, but you can spend time learning, practicing, honing your skills. If you’re going to spend that time, why not ask how Leonardo spent his time?

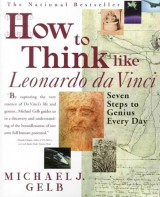

In his book How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci, Michael J. Gelb has already researched the methods Leonardo used and distilled them into principles. You need to get this book and read it to understand the seven principles. As you read the book, you’ll be able to extrapolate how each one applies to writing fiction. Here are those seven principles:

In his book How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci, Michael J. Gelb has already researched the methods Leonardo used and distilled them into principles. You need to get this book and read it to understand the seven principles. As you read the book, you’ll be able to extrapolate how each one applies to writing fiction. Here are those seven principles:

- Curiosità: An insatiably curious approach to life and an unrelenting quest for continuous learning

- Dimonstrazione: A commitment to test knowledge through experience, persistence, and a willingness to learn from mistakes

- Sensazione: The continual refinement of the senses, especially sight, as the means to enliven experience

- Sfumato: A willingness to embrace ambiguity, paradox, and uncertainty

- Arte/Scienza: The development of the balance between science and art, logic and imagination; “whole-brain” thinking.

- Corporalita: The cultivation of grace, ambidexterity, fitness, and poise.

- Connessione: A recognition of, and appreciation for, the interconnectedness of all things and phenomena; systems thinking

Just reading through the list should remind you of what you know about da Vinci. Leonardo never wrote down these principles himself; he was far too disorganized for that, though he intended to get around to it someday. Michael Gelb developed the principles from what is known of da Vinci’s life.

Even the bare descriptions of each principle should suggest to you how each one applies to writing fiction. Maybe you’re scratching your head at the Corporalita principle, wondering how that one relates to a sedentary activity like writing. It does, trust me. I will devote seven future blog posts to a discussion of each principle, and how you can use each one to improve your fiction writing.

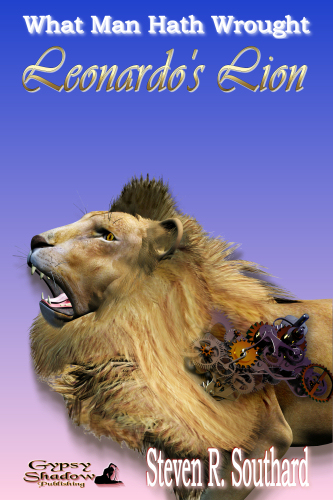

At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story, “Leonardo’s Lion,” deals with the question of what eventually happened to that clockwork marvel.

At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story, “Leonardo’s Lion,” deals with the question of what eventually happened to that clockwork marvel.

Right after you buy my book, buy How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci, and get started writing with the skill of your inner genius. When you become famous and people ask how you learned to write so well, be sure to tell them it was all due to a blog post written by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense.

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense. The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility.

The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility. Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “

Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “