Many great writers suffered early in life and during their writing careers. Of these, a good number wrote from a place of suffering, capturing that pain and creating timeless novels.

Did their suffering lead to classic writing? If so, would these authors have written so well if not for their suffering? In other words, is personal suffering necessary to produce great art?

Brian Feinblum explored this topic in a blogpost, and that’s what inspired my post today.

What about those of us who have led relatively happy and disease-free lives? Do we lack the necessary ingredients to produce great fiction?

The list of writers who suffered from health ailments alone (never mind other sorts of problems) is long. Here’s a partial list:

- John Milton—likely a detached retina leading to blindness

- Jonathan Swift—Ménière’s Disease leading to vertigo and tinnitus, obsessive-compulsive disorder

- The Brontë Sisters—tuberculosis and depression; one may have had Asperger’s Syndrome.

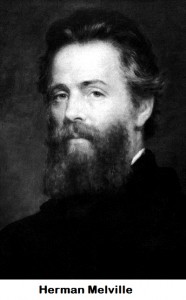

- Herman Melville—pains in joints, back, and eyes due to Ankylosing Spondylitis which brought on depression

- Fyodor Dostoevsky—epilepsy, gambling addiction, severe depression

- Jules Verne—stomach cramps from colitis, painful facial paralysis from Bell’s Palsy

- Edith Wharton—typhoid fever, asthma

- Jack London—bipolar disorder, scurvy, alcoholism, leg ulcers

- Virginia Woolf—depression, mood swings, hallucinations

- James Joyce—eye problems after gonorrhea treatments

- F. Scott Fitzgerald—heavy drinking, heart disease

- Ernest Hemingway—depression, alcoholism, electroshock treatments

- George Orwell—damaged bronchial tubes after childhood bacterial infection, tuberculosis

- Tennessee Williams—depression, drug and alcohol addiction

- Sylvia Plath—depression; shock therapy; several suicide attempts

Perhaps your life doesn’t include any ailments nearly as severe as any on that list. Does that eliminate you from contention on some future list of great authors?

Fiction revolves around conflict, and therefore fictional characters must suffer. That’s necessary so readers can believe in them, identify with them, and root for them during their struggles.

Writers with health problems may have an edge here. They can write out of their own painful experiences. They’ve gazed into the abyss themselves, and garner instant credibility.

However, not all people who’ve suffered end up as successful novelists. Further, not all great writers suffered from anything more severe than the typical pains of a normal life.

I think what matters more is your ability to identify deeply with a suffering character you’ve created, and to convey that suffering to readers with your words. That strong empathy will come through, and distinguish your writing.

You needn’t have endured intense personal suffering to create great fiction. Make your protagonist suffer, though, and convince your readers to care about that character.

Hellen Keller knew something about the subject, and wrote, “Although the world is full of suffering, it is also full of the overcoming of it.”

You may not have suffered as she did, but you can write. On the journey toward great fiction writing, whether you’ve suffered or not, you’re free to join—

Poseidon’s Scribe