What is a MacGuffin, do you want one in your story, and if so, how do you incorporate one? Read on to find out about this literary term.

Simply put, a MacGuffin is the protagonist’s goal. It can also be the goal of the antagonist as well. Perhaps they’re both pursuing it, or seeking to prevent the other from having it. It can be a tangible object, or an abstract idea.

Simply put, a MacGuffin is the protagonist’s goal. It can also be the goal of the antagonist as well. Perhaps they’re both pursuing it, or seeking to prevent the other from having it. It can be a tangible object, or an abstract idea.

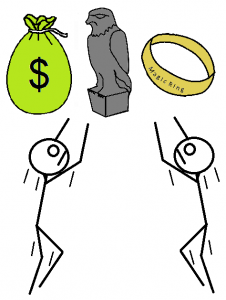

Examples of MacGuffins in literature and film include the falcon figurine in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, the witch’s broomstick in the film “The Wizard of Oz,” and the Golden Fleece in Apollonius Rhodius’ epic poem “Argonautica.”

Some stories have more than one MacGuffin, and characters seek them in sequence, one after the other. This is common in fantasy stories and fantasy games. Multiple MacGuffins are termed plot coupons.

A character’s goal (the MacGuffin) is different from a character’s motivation. As author Starla Criser explains, a goal is what you want. A motivation is why you want it. We’re mostly talking about the goal here, but it’s important that you convey to the reader that your character has a good reason to pursue that MacGuffin.

There remains some confusion over the term MacGuffin. In the Wikipedia article, director Alfred Hitchcock seems to dismiss it as unimportant—“The audience don’t care.” Director George Lucas disagrees, saying viewers should care about the MacGuffin as much as they do the main characters.

Author Michael Kurland resolves this confusion well in his article about MacGuffins. He says it’s important for the writer to establish why the MacGuffin is vital to the character early in the story. Regardless of the reader’s actual feelings about the MacGuffin, it’s vital that the reader understand its importance to the character. After that point, writers should emphasize the plot and the characters to give life and vitality to the story, and the MacGuffin can fade in significance.

The Wikipedia article states that the protagonist’s pursuit of the MacGuffin often has little or no explanation. I can understand little explanation, but none? The reader has to know the reason for the character’s hunt; otherwise, why should the reader care about the character at all?

Now you know the answer to the question I posed in the title of this blog post. Yes, you do know the MacGuffin Man. He lives in Literury Lane, of course! Address all complaints about bad puns to—

Poseidon’s Scribe