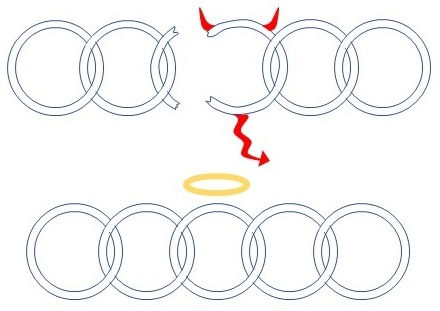

Do you recall one of your physics teachers mentioning the concept of entropy? Today I’d like to discuss its opposite, negentropy, and how that applies to writing.

Entropy depresses me. I dislike the idea that energy changes into less and less useful forms, that order becomes chaos, and that the universe eventually runs down and stops.

Negentropy seems more fun. While we all wait for the universe to wind down, we can take tiny chunks of it and turn chaos into order within those chunks.

I ran across this article by Dr. Alison Carr-Chellman where she explores the concept of negentropy as it applies to everyday things like cleaning your room or making your workplace run smoother. I wondered if her concepts could apply to writing fiction.

Writing, itself, epitomizes negentropy. The inputs—life experiences, a brain, and writing implements—get converted to a single output, fiction. Chaos becomes order.

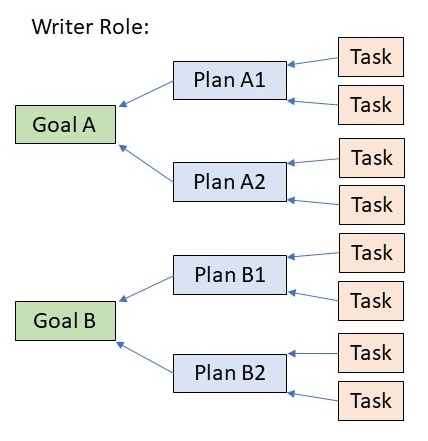

But is your fiction-producing process smooth and efficient? Are you losing energy along the way? Think about achieving maximum output (published fictional stories) for minimum input (personal time and energy).

Dr. Carr-Chellman provides five steps for improving that efficiency (she calls it ‘minimizing energy loss’). I’ll discuss each as they apply to writing fiction.

1: Find the entropy. Think of the steps involved in getting to a published story. Which of those steps (examples: researching, editing) take the most time for you? Which do you put off or rush through (ex: scene setting, choosing a title) because you hate doing them? Which steps do you agonize over (ex: submitting, marketing) because you don’t understand them well?

2: Prioritize the losses. Identify the biggest entropy problems, so you tackle them first. Not only will this provide the best gains in efficiency, but your success will embolden you to solve the others in a similar manner.

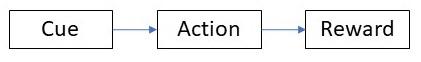

3: Come up with a plan. For the steps taking too much time, consider self-imposed time limits. For the steps you hate, give yourself small rewards for completing them. For the steps you don’t understand well, learn about them from TED talks, YouTube videos, books, or internet searches.

4: Try it out and pay attention. As you implement your improvement plans, track how they’re working. Did you put more energy and time into the plan itself than the improvement warranted?

5: Go beyond fixing and maintenance. As you plug all these energy leaks and achieve a smoother process, consider the bigger picture. Perhaps you’ve now developed a very efficient method for selling low-grade stories. That may not have been your desire. It’s not worth optimizing a process that doesn’t result in the output you want.

If you start implementing negentropy into your writing now, you stand a great chance of optimizing it before maximum entropy brings about the heat death of the universe. That event may happen as soon as ten to the hundredth power years from now. That’s a googol years. Best not to schedule anything in your personal organizer for any date after that event.

Negentropy, turning chaos into order. That’s the main job of—

Poseidon’s Scribe