It’s vital to read your story aloud before submitting the manuscript for publication. You may consider that a waste of time, since you can  read the story silently to yourself more easily, and because silent reading is the way most readers will experience your work as well.

read the story silently to yourself more easily, and because silent reading is the way most readers will experience your work as well.

I contend you really should take the time for reading aloud, and for making that technique one of your final editing methods. For several of the reasons below, I’m indebted to Joanna Penn.

- After reading your story silently several times, reading aloud will give you the different perspective of the spoken word, enabling a more thorough edit.

- You’ll find it easier to spot story inconsistencies and plot continuity problems.

- With this different style of reading, you’ll find the typos and punctuation errors you skipped over earlier.

- You’ll hear more readily if your story’s dialogue is realistic or forced.

- The need to breathe when speaking will aid you in identifying overlong sentences.

- You’ll have an improved sense of whether you’re building tension effectively.

- By timing your reading, you’ll know how long the audiobook or podcast version of your story will be.

- You’ll find right away if you have any tongue-twisting phrases or words that sound jarring when juxtaposed.

- By saying words aloud, you’ll likely have a better notion of which ones to emphasize by italicizing.

- You’ll better hear the rhythms of the words and sentences, the cadences of your story, and might identify edits to make them flow better.

You might be thinking you’ll have a friend read your story to you, or get a software program to read the text aloud, while you just listen and let the words wash over you. I advise against that and recommend you read the story with your voice, letting the words tumble from your own lips. Both speaking and listening will give you a stronger mental connection with the story than mere listening would.

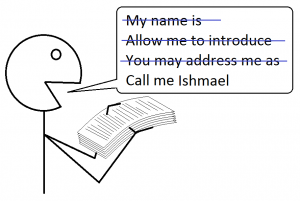

If you’re one of the few writers who doesn’t regularly employ this technique, I recommend you join the majority. It will improve the quality of your stories, and that guarantee is straight from the mouth of—

Poseidon’s Scribe