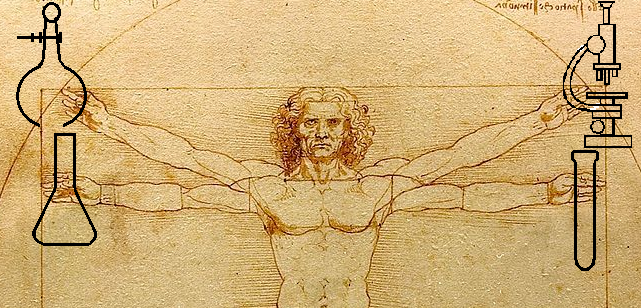

We’re continuing today with my series of blog posts discussing the principles of How to Think like Leonardo da Vinci, by Michael J. Gelb, and how they relate to writing fiction. Today’s principle is Dimonstrazione, a commitment to test knowledge through experience, persistence, and a willingness to learn from mistakes.

It’s not enough just to be curious about people and the world, as the first principle of Curiosità advocated. You must add to your knowledge and seek truth by testing and experimentation.

It’s not enough just to be curious about people and the world, as the first principle of Curiosità advocated. You must add to your knowledge and seek truth by testing and experimentation.

In our current Age of Information, it’s so easy to accept the word of experts, to trust Wikipedia, etc. But Leonardo da Vinci didn’t put his faith in the word of others. He put things to the test. He experimented and tried things for himself.

How does this apply to your fiction writing efforts? The world, the web, and even my own website are all full of advice for beginning writers. But no one knows what novels will catch on next year. Your ideas about what might become a bestseller may conflict with every bit of common knowledge out there, but you might be right.

You have to be willing to try things, different things, bizarre things. If they work, ride that wave and keep doing them, even if the professionals advise against it. If they don’t work, stop doing them, even if it means disregarding every expert in the world.

Here are several ways you can employ Dimonstrazione in your writing life:

- If you’re trying to find out writing habits that work the best for you, try writing at different hours of the day, in different locations, for different lengths of time, using different word processors (or even pen and paper), etc. Find what works best and stick with that.

- Realizing that some people accept the principle of Dimonstrazione and others don’t, make that a contrasting trait between two characters in a story—one who won’t accept authority and puts established knowledge to the test, and the other who accepts the word of authority as fact.

- To determine what your ‘voice’ is, try different voices. See which one your readers respond to best.

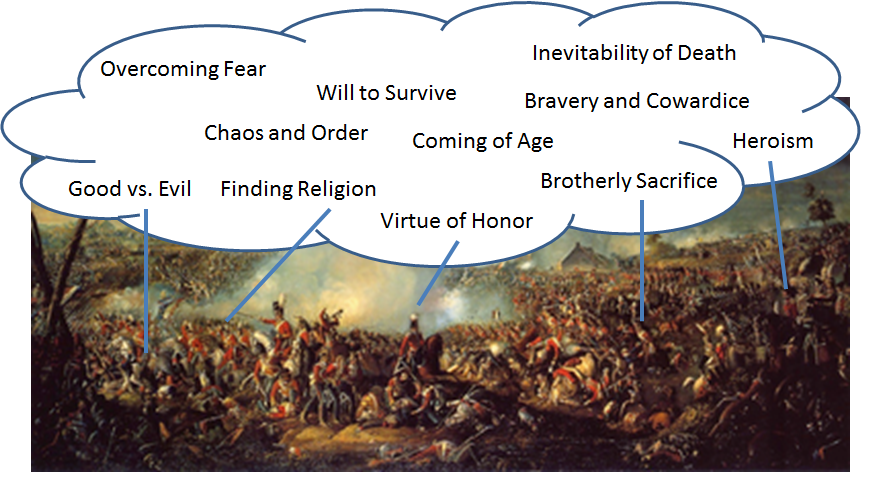

- If money or fame are not important to you and you only write for enjoyment, find those genres, plot types, themes, settings, and character types that give you the greatest pleasure to write about.

- If you’re trying to increase your readership, experiment with the various elements of fiction (plot, character, setting, theme, and style) and see which stories sell the most copies.

- What are the best conferences for you to speak at? Try several, and see which one causes the biggest uptick in sales.

- If you don’t know what type of free book giveaway will result in the largest e-mail list, try different types of giveaways—different rules, etc.

- Study the market and see what’s working for other authors. Don’t copy everything they do, but consider changing your methods to get a little closer to their way of doing things.

The important thing about Dimonstrazione is its philosophy, its approach to understanding knowledge. When you read or hear the advice of an authority, be skeptical and apply some critical thinking. If you believe the truth is different than what the authority says, test it for yourself. If the experiment proves you wrong, admit your error and adjust your beliefs.

Through persistent application of Dimonstrazione, you’ll start to think more like Leonardo da Vinci, or at least more like—

Poseidon’s Scribe