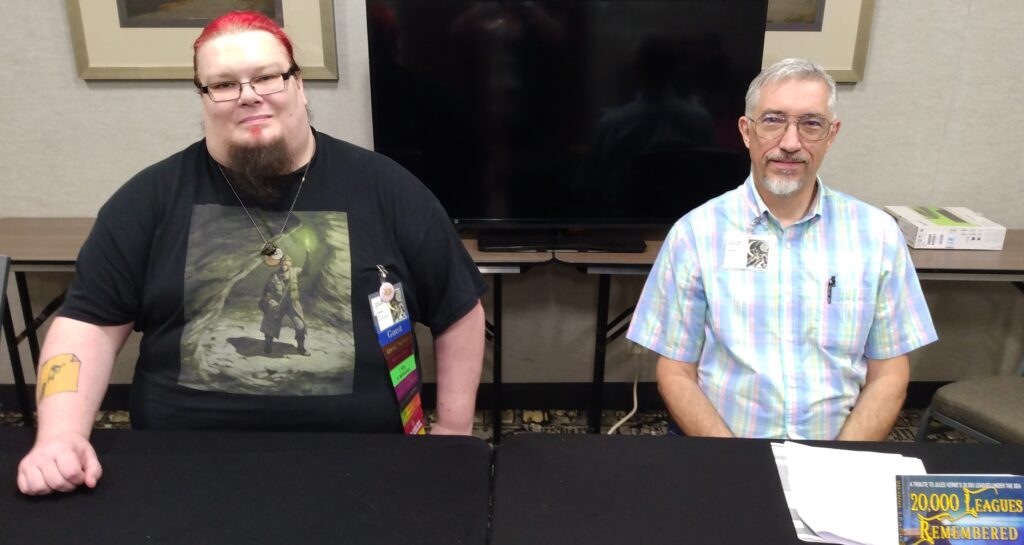

It may seem like I conduct these author interviews within a plush studio high atop Poseidon’s Scribe Tower at Poseidon’s Scribe Enterprises. In truth, for most of them, I only communicate with these writers by email and have never encountered them in person.

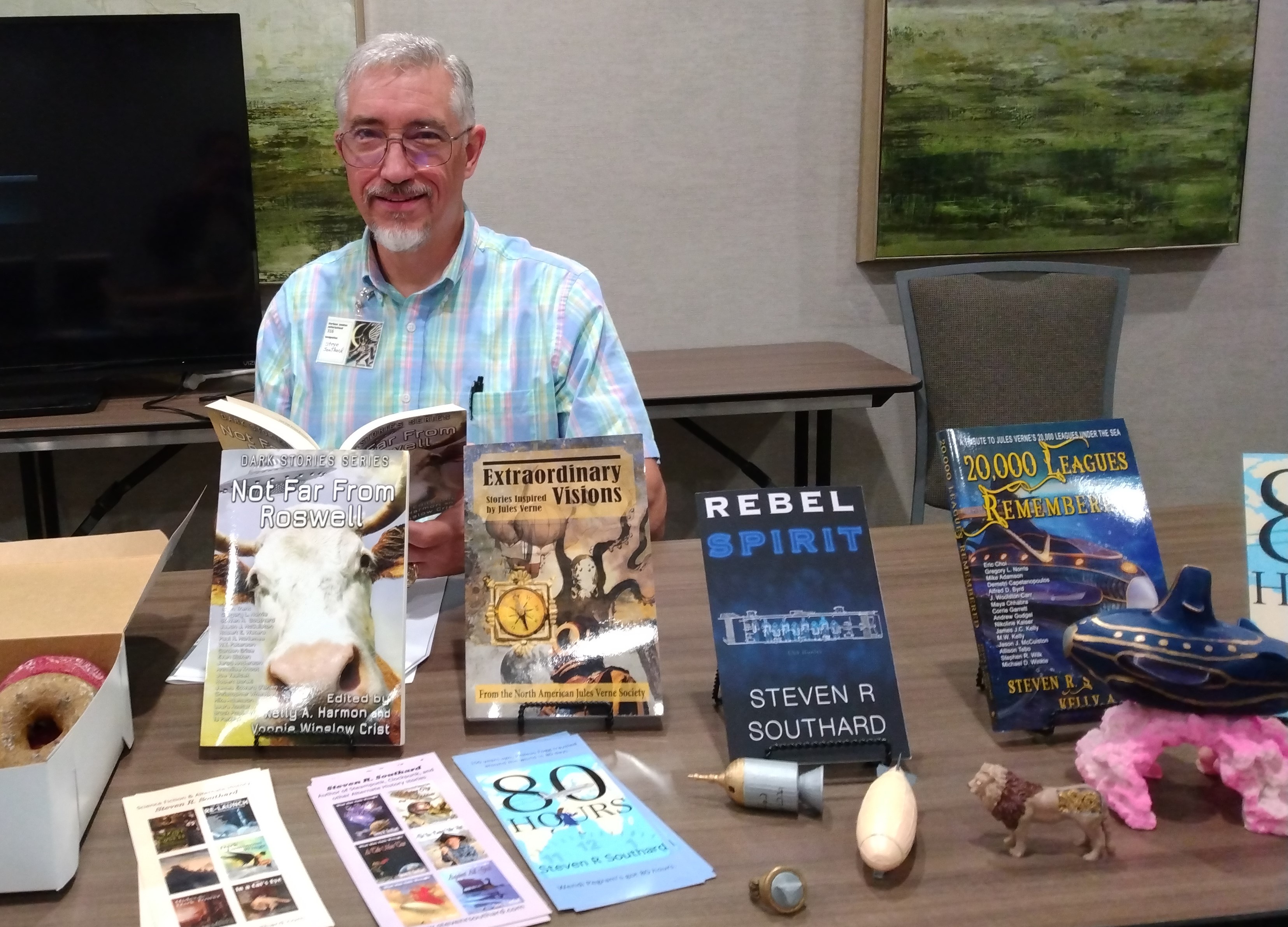

But I’ve actually met today’s featured author. We served as panelists together at PenguiCon 2023, where Eric Choi was a guest of honor. A story of his appears in both anthologies I’ve edited—20,000 Leagues Remembered and Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne.

Eric Choi is an award-winning writer, editor, and aerospace engineer in Toronto, Canada. He was the first recipient of the Isaac Asimov Award (now the Dell Magazines Award) and he has twice won the Aurora Award for his story “Crimson Sky” and for the Chinese-themed speculative fiction anthology The Dragon and the Stars (DAW) co-edited with Derwin Mak. With the late Ben Bova, he co-edited the hard SF anthology Carbide Tipped Pens (Tor). His short story collection Just Like Being There (Springer Nature) was released last year. Visit his website or follow him on social @AerospaceWriter.

Next, the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing fiction?

Eric Choi: My start in fiction writing is owed to the Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Excellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy (formerly the Isaac Asimov Award). I was the very first recipient of the Dell/Asimov Award for a story called “Dedication”, which was about a team of astronauts on Mars struggling to survive after their rover is damaged in a meteorite shower. The story was published in Asimov’s Science Fiction and years later it was reprinted in Japanese translation in the anthology The Astronaut from Wyoming and Other Stories. I am forever grateful to Rick Wilber, Sheila Williams, and the late Gardner Dozois for starting my fiction writing career.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences?

E.C.: My background is in aerospace engineering, and many of my greatest influences have been other engineers and scientists. The British website SF2 Concatenation has an excellent series of articles by science fiction writers with a degree in science, engineering, mathematics, or medicine about the top ten scientists and engineers who have most inspired or influenced them. Those who influenced me were profiled in an article in the Summer 2019 edition and include aeronautical engineer James Floyd, astronomer Carl Sagan, my undergraduate thesis supervisor James Drummond, atmospheric scientist Diane Michelangeli, Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman, and astronaut Sally Ride.

P.S.: What are a few of your favorite books?

E.C.: My leisure reading tends to include a lot of non-fiction. I am currently reading Cobalt Red by Siddharth Kara about the appalling conditions in which the cobalt for lithium-ion batteries is mined, and The New Guys by Meredith Bagby about the historic NASA astronaut class of 1978 that recruited the first Black, Asian, and female American astronauts. Some of my favorite non-fiction books include The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre about the KGB double agent Oleg Gordievsky who changed the course of the Cold War, Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly about Katherine Johnson and the other Black female mathematicians and engineers who played crucial roles in the early U.S. space program (the movie doesn’t do the story justice), 747 the memoir of aeronautical engineer Joe Sutter, Thread of the Silkworm by Iris Chang about the Chinese rocket scientist Qián Xuésen (the subject of my alternate history story “The Son of Heaven”), A Man on the Moon by Andrew Chaikin which is my favorite history of the Apollo program, and Bush Pilot with a Briefcase by Ronald Keith about the Canadian aviation pioneer Grant McConachie (a fictionalized version of whom appeared in my alternate history story “The Coming Age of the Jet”).

P.S.: Does your day job as an aerospace engineer help you with your fiction writing, or interfere with it?

E.C.: Science fiction inspired me to pursue a career as an aerospace engineer. Over the course of my day job I’ve had the privilege of working on a number of space projects including the QEYSSat satellite, the Phoenix Mars Lander, the Canadarm2 on the International Space Station, the RADARSAT-1 satellite, and the MOPITT instrument on the Terra satellite. I guess you could say that some parts of my day job are a bit like a science fiction, so the fiction writing is really coming full circle. There have always been important linkages between science fiction and the real-life space program. Our knowledge of the Universe, our attitudes towards science, and our understanding of science and technology are some of the key influences on science fiction. In turn, science fiction has helped shape perceptions of the space program, in some cases influencing the politics and funding of space projects and even the design of the missions themselves, as well as inspiring people like me to pursue careers in engineering and science. So if there is interference, it is most certainly a constructive interference.

P.S.: In addition to your fiction, you’ve written a number of technical papers associated with your aerospace job. Since fiction is so different from professional, scientific nonfiction, how difficult is it for you to transition between the two types of writing?

E.C.: There are actually a lot of similarities between writing fiction and writing technical papers. A work of fiction has a narrative arc with a beginning, a middle, and an end. But a technical paper has an arc as well – an introduction, a description of methodology, a presentation of data, and a discussion of results. And if you think about it, both are telling a story in their own way that is most compelling and convincing to their respective audiences.

P.S.: You got to co-edit an anthology with Ben Bova! What was that experience like?

E.C.: I first met Ben Bova at the 2011 Ad Astra science fiction convention in Toronto, where I found myself sharing an author signing table with him (presumably because of the alphabetical order of our surnames). There was a huge queue of fans for Ben and almost none for me (which meant that everything was right in the Universe), but I managed to make some small talk in the rare moments when he wasn’t giving his time to his readers. What I really wanted to talk to him about was an idea I had for a hard SF anthology, but I couldn’t quite get the nerve. Finally, like an awkward teenager asking for a date, I managed to blurt out my idea and asked if he might be interested in working with me.

He said yes.

Our hard SF anthology Carbide Tipped Pens was published by Tor three years later, and I had found a mentor and a friend. Ben’s name rightfully came first on the cover, but he would often say to people “it’s really Eric’s book”, an act of genuine kindness that would leave me in a state of Heisenbergian uncertainty somewhere between impostor syndrome and bemused pride. I only knew Ben for a few years, just a short moment in the grand tour of his remarkable life, but that’s all friends need.

I was deeply saddened by Ben’s passing in November 2020. His death was due in part to the consequences of a pandemic whose effects had been made far worse by selfishness, science denialism, and outright lies – all things antithetical to Ben’s generosity, wisdom, and honesty. As writers and readers of science fiction, I hope we can honor Ben Bova’s memory by paying it forward and being voices for fact-based reason and science in the service of humanity.

P.S.: Many of your short stories, including “Raise the Nautilus,” involve elements of alternate history. What draws you to exploring science-themed alternate histories? What are some of the challenges?

E.C.: If science fiction is the literature of scientific and technological possibility, then the appeal of science-themed alternate history is in exploring how scientific and technological possibility influences the relationship between chance and determinism in shaping historical events. It is, however, a challenging genre to write. Not only do authors need to get the science right, but they must also recognize the sensitivity of putting real people into fictional situations. Authors of alternate history have an obligation to be careful in their portrayals of real people and ensure that the words and actions of historical figures are consistent with what is known about them from the historical record. For example, my Aurora Award nominated novelette “A Sky and a Heaven” is an alternate history about the Space Shuttle Columbia accident. I changed the name of the commander of Columbia because in an early draft of the story this person did something that I felt was inconsistent with the personality of the real commander Rick Husband.

P.S.: A story of yours appears in the new anthology Life Beyond Us. Tell us about that one.

E.C.: Life Beyond Us is a new astrobiology-themed science fiction anthology from the European Astrobiology Institute and Laksa Media Groups edited by Julie Nováková, Lucas K. Law, and Susan Forest. The book features twenty-seven stories, each accompanied by an essay written by a scientist in a relevant field. My story “Hemlock on Mars” opens the collection with the accompanying science essay “Planetary Protection: Best Practices for the Safety of Humankind (And All Those Aliens Out There)” by Giovanni Poggiali of Observatoire de Paris. Planetary protection is the practice of safeguarding Solar System bodies from contamination by Earth life as well as protecting Earth from possible lifeforms that might be brought back from other Solar System bodies. In “Hemlock on Mars”, a hardy microbe is found in the clean room where a mission to search for life on Mars was assembled. It may have hitched a ride on the spacecraft. It might survive on Mars. It might compromise the primary life detection science investigation. Worse, if there is any indigenous Martian life, it might harm it. But it might not be present on the spacecraft at all. If it is, it might not survive the journey. It might well not survive on Mars. And Mars today is probably lifeless, but we’re not entirely sure. Do they pull the plug on a very expensive mission that promises to answer one of humanity’s most profound scientific questions? Or do you let it land and risk contaminating Mars with a potentially harmful terrestrial organism?

P.S.: Your story, “Raise the Nautilus” appears in two anthologies—20,000 Leagues Remembered and Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne. Readers of this blog already know about the story, but may not know the real-life events you researched to write it. Please tell us about those.

E.C.: In “Raise the Nautilus”, the British Royal Navy attempts to salvage Captain Nemo’s submarine and retrieve an artifact that could turn the tide of the First World War. The title and theme of the story were influenced by the 1976 Clive Cussler novel Raise the Titanic in which a team attempts to salvage the ocean liner and recover a substance that could tip the balance of power during the Cold War. The fictional operation to recover the Nautilus was based on the real-life salvage of the USS Squalus, a U.S. Navy diesel-electric submarine that sank during a test dive off the coast of New Hampshire in May 1939. 26 sailors were killed, but the lives of the remaining 32 crewmembers and one civilian were saved over the course of a 13-hour rescue operation using a diving bell called a McCann Rescue Chamber. The Navy then undertook a long and difficult salvage operation over the course of the next four months in which the Squalus was eventually raised and towed to the Portsmouth Naval Yard. Following extensive repairs, the submarine was recommissioned as the USS Sailfish and went on to serve in the Pacific theatre during the Second World War.

P.S.: Your recently published collection Just Like Being There contains a novelette and several short stories, including “Raise the Nautilus.” What would you like readers to know about this collection?

E.C.: Just Like Being There is my first collection of short fiction and features fifteen of my hard SF and alternate history stories including the Aurora Award short story winning “Crimson Sky” and the Aurora Award nominated novelette “A Sky and a Heaven”. Story topics include space exploration, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, cryptography, quantum computing, online privacy, mathematics, neuroscience, psychology, space medicine, extraterrestrial intelligence, undersea exploration, commercial aviation, and the history of science. Each story is followed by an afterword that explains the underlying engineering or science.

Putting the collection together was tremendous fun but also a lot of work. The novelette “A Sky and a Heaven” was a new story and the longest piece I have ever written. For the other fourteen previously published stories, I went back to the manuscripts as I had originally written them and in some cases made minor revisions. As an example, I moved out the dates in a near-future space exploration story called “From a Stone” because as of the publication of the collection humans have not yet resumed crewed voyages beyond low Earth orbit. In general, however, I was pleasantly surprised at how well my stories have held up over time. What took the most time and effort was writing those afterwords that discuss the engineering and science behind the stories. I was fortunate to still have much of the original research material for the stories, but I also did new research to make sure the information was as up-to-date as possible.

P.S.: What tales can we expect from you in the near future?

E.C.: My new story “Random Access Memory” about people who experience an unusual phenomenon while playing a certain slot machine at a casino will be appearing in the upcoming anthology Game On! edited by Stephen Kotowych and Tony Pi. Another new story called “Beware the Glob!” about a dangerous extraterrestrial creature that is unleashed from its frozen Arctic slumber by climate change will appear in the September/October 2023 issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring writers?

Eric Choi: Robert A. Heinlein’s first enunciated his famous rules for writers in 1947 and they are still applicable today. To paraphrase: You have to write, you have to finish what you write, you must not allow yourself to get stuck in an endless cycle of rewrites, you have to put what you write on the market, and you have to keep putting your work out there until it’s published. That last part is particularly important. Rejection is an inherent part of writing and you must never let it discourage you. To this day, my own rejection to acceptance ratio averages about 7 to 1. The important thing to remember is that rejection often has nothing to do with the quality of your work or your skill as a writer but rather the fit of the story with a particular market or publication. If you are fortunate to receive constructive feedback, revise your work as you see fit (it’s always a writer’s prerogative to incorporate or ignore external comments) and then send it back out there until it’s published.

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thank you, Eric.

Readers can find out more about Eric Choi at his website, on Amazon, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram. Read Eric’s interview by Analog editor Emily Hockaday, and Eric’s list of the best books on aviation and space history.