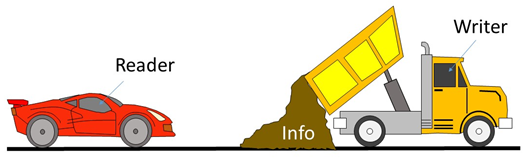

You’re reading along down the story highway, racing through action scenes, taking the dialogue curves at a good clip, the wind of the story’s world in your hair. All of a sudden, a truck up ahead upends its load and a pile of text pours onto the pavement, right in your path.

You’ve been stalled by an infodump.

You come to a stop to decide what to do. You could plow right through it at slow speed, but you hate that. You could drive around, avoiding it entirely, but some of that text might be necessary to understand the story. If you’re in an angry mood, you could forget the whole book and move on.

An Infodump is one of the Turkey City Lexicon terms. It refers to a passage of text used to explain things and give background information to the reader. It can be one paragraph, or go on for several pages. It’s most common in science fiction and fantasy, where the story’s world is unlike our own, and you need to immerse the reader in it.

From a writer’s perspective, it seems so necessary to convey that information. The reader needs to understand certain things so later events in the story make sense. Many of the great writers of the past used infodumps; Herman Melville spent whole chapters that way, and it hasn’t hurt his sales. Oh, perhaps the writer could think of clever ways to work the information into the story, but who has time for that?

Better make time, you Twenty-First Century Writer, because readers these days don’t want to slow down and plow through your dump.

Here are some techniques:

- Delete it. What does that info add to your story, anyway? Do readers really need to know it? Are you dumping that load to help reads understand, or to show off your research or add credibility? If you can delete it, do so. If you can delete most of it, do that, and use other techniques to convey the rest.

- Work it into dialogue. Readers speed through your characters’ dialogue pretty fast, so inserting some of your infodump into their speech is one way to avoid slowing readers down. Caution: there’s danger here. You must not swerve into the As You Know, Bob lane. Make sure the dialogue is realistic as well as explanatory.

- Work it into the action. By ‘action’ I don’t necessarily mean fight scenes or car chases, but any passages where characters are doing things, moving about, or actively interacting with their environment or each other. It’s characterized by action verbs. It can be interspersed with dialogue, and often serves as a ‘dialogue tag,’ letting the reader know which character is speaking.

- Make it entertaining. If you can turn those smelly tons of interfering text into pure, golden fun, readers will actually enjoy the interruption. By ‘entertaining,’ I don’t necessarily mean funny, but humor is a great way to accomplish this, if you can pull it off. This method calls for considerable creativity and skill.

- Make it short. As a last resort, keep the infodump, but reduce its length. Readers may forgive a short, explanatory passage here and there.

I struggle with infodumps in my fiction, but it’s important to eliminate them where possible. Dump trucks are fine in real life, but when they drop their load in the middle of your story’s road, it really ticks off your readers. Not good.

Doing my part to beautify the nation’s literary highways and byways, I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe