No way, you’re thinking. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a genius, a child prodigy, a composer whose fame will endure forever. There’s no way you could write fiction one eighth as well as he composed music.

Maybe not, but I’m suggesting you could aim for that end, strive to emulate his method. To the extent you can do that, you might well end up writing fiction beyond your current abilities.

How did Mozart compose music? He said, “I write music as a sow piddles,” which speaks to how naturally it was for him, but gives no hint of method. There is evidence he used sketches and did his main composing at a keyboard, but it’s also clear he had an amazing memory.

A scene from the 1984 movie Amadeus provides a hint of how he might have composed. I know it’s fiction, a movie, but it’s based on reality. I’ve long admired the scene; you can see it on YouTube, though you should watch the whole film.

A scene from the 1984 movie Amadeus provides a hint of how he might have composed. I know it’s fiction, a movie, but it’s based on reality. I’ve long admired the scene; you can see it on YouTube, though you should watch the whole film.

In that scene, Mozart is gravely ill, bedridden, too weak to write. With the assistance of rival composer Antonio Salieri, he’s trying to compose the Confutatis movement of the Requiem in D minor. While Mozart describes, and sings, the various parts, Salieri scribbles as fast as he can. Repeatedly, Mozart asks, “Have you got it?” and Salieri keeps saying, “You’re going too fast.” In the background, the audience hears an orchestra and choir performing the fast-developing piece.

Mozart seems to be conveying a piece already fully formed in his mind. His task seems not to create or invent, but to capture and document. Speed is of the essence to him, not because he will forget any part of the piece, but because his health is failing and he’s running out of time.

One could surmise his entire composing career might have gone at a breakneck pace, even during his healthy times. He only lived to age thirty five, and it seems as if he were born with a century of music in his mind, but permitted only a third of that time to document it for others.

Here’s a thought experiment. Imagine if that were also true for you. What would it be like to have short stories, novels, and novellas already finished in your mind, every word clear and instantly retrievable? You don’t face a quality problem, for all those tales are perfect in structure, irresistible to readers. Nor do you have to struggle to invent characters, plots, or settings, let alone agonize over word choices or sentence formations. That’s all done.

Your only difficulty is writing them all down. You only need one draft—no editing—but there are too many stories. You have three lifetime’s worth of tales to scribble, but your hands and fingers will only last a single lifetime.

That was an enjoyable daydream, wasn’t it? However, you’re no Mozart, and neither am I. We toil away on draft after draft. The stories in our minds are but half-glimpsed, ghostly figments of perfect tales, and our attempts to recreate them in text are pitifully botched versions of those images. Our lifetimes of writing are spent slowly learning and honing the aspects Mozart found trivial.

At least we can envision what it might be like to be Mozart. If we can envision that, we can strive toward it, work to approach closer to it. It seems to me there are three aspects of Mozart’s abilities to work on: (1) attaining complete works in your mind, (2) ensuring those visions are in final form, and (3) conveying the vision to text rapidly.

Here are some exercises to develop each aspect:

- 1A. Do as much story planning as you can—setting details, character traits and appearances, major plot points—before writing anything down.

- 1B. Get the next sentence fully formed in your minds, and memorize it, before writing it down.

- 2A. Practice editing a sentence at a time in your mind, trying various word substitutions, word orders, and structures, before writing the sentence down.

- 2B. Work on limiting the number of drafts you go through before declaring a story done.

- 3A. Participate in NANOWRIMO, and write a novel of at least 50,000 words during only the month of November.

- 3B. Try writing software such as Write or Die or Flowstate, word processors that penalize you for getting distracted while writing.

I’m not guaranteeing these exercises will enable you to produce stories on par with Mozart’s music. Still, what if they made you half as good? Even a quarter as good? Writing stories one eighth as good as Mozart’s musical pieces is a lofty goal for—

Poseidon’s Scribe

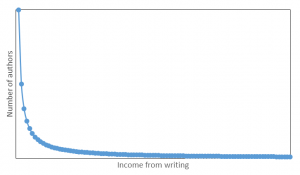

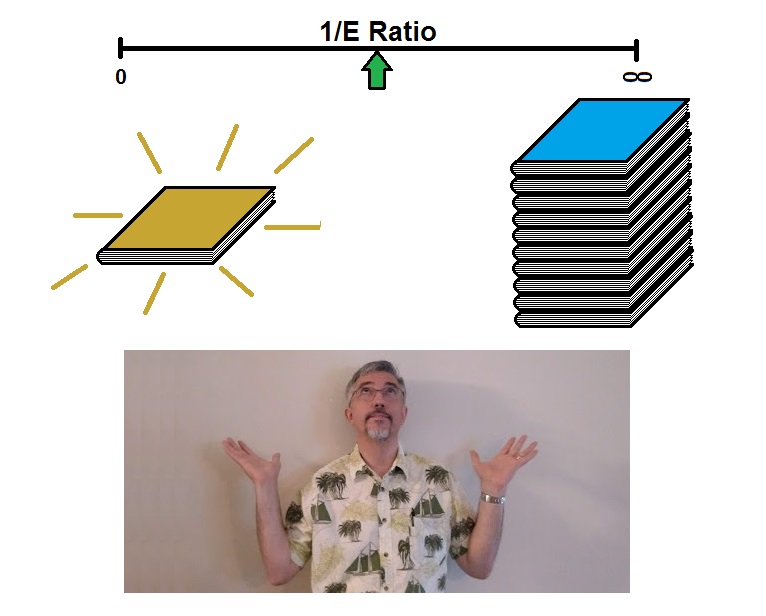

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times.

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times.