A significant proportion of the Homo sapiens species does not write fiction, leaving that task to a tiny sector of the population that writes all of it. Today we examine this phenomenon and these particular creatures, and draw what conclusions we can from the available data.

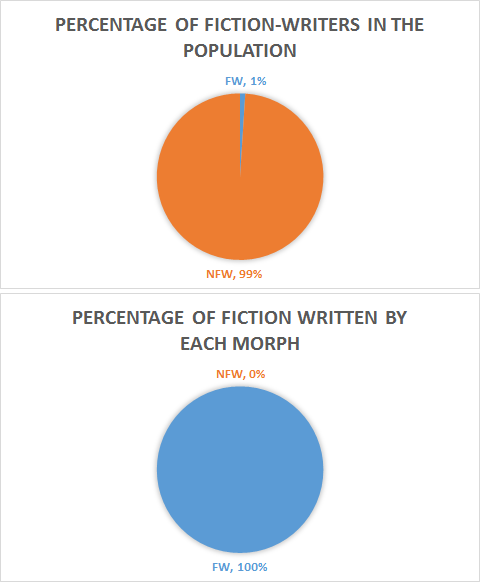

Observations indicate the vast majority (greater than 99 percent) of adults within this species do not write fiction. The fiction-writing and non-fiction-writing fractions have not split off as separate species, and seem unlikely to do so. The distinction between the two is behavioral only, so we may define the fiction-writers as the FW Morph, and the others as the NFW Morph. Other sub-species terms such as breed, race, cultivar, ecotype, and strain are not as applicable as morph.

Observations indicate the vast majority (greater than 99 percent) of adults within this species do not write fiction. The fiction-writing and non-fiction-writing fractions have not split off as separate species, and seem unlikely to do so. The distinction between the two is behavioral only, so we may define the fiction-writers as the FW Morph, and the others as the NFW Morph. Other sub-species terms such as breed, race, cultivar, ecotype, and strain are not as applicable as morph.

Note: We are only comparing those Homo sapiens who write fiction and those who do not. The term NFW should not be confused with those who write nonfiction books.

FWs and NFWs coexist and both share a similar global distribution pattern. Evidence shows the two morphs consume similar food, display no distinctive appearance differences, and often cohabit and interbreed without apparent preference for their own, or the other, morph. Resulting offspring mature into FW or NFW in the same 1% and 99% proportions, respectively. No statistical correlation is observed regarding passing on the FW trait to offspring. For example, two NFW parents may produce a child who matures into a FW.

In general, the species puts significant value on the education of its young. Nearly all juvenile Homo sapiens are trained in fiction writing, and are encouraged to create their own stories between the ages of 8 and 18 years. Thus, nearly all have the capability to become FW as mature adults, yet few do.

Behavioral differences between the two morphs are significant, and some of these differences are documented below.

- Obviously, FWs spend considerable time writing fiction, and NFWs spend no time doing so.

- FWs are more likely to read books (both fiction and nonfiction), and to read more often, than NFW.

- FWs react in varied and bizarre ways to the acceptance of a submitted story by an editor, and to the arrival of a box of the FW’s own books. These apparent rituals (dancing, fist-pumping, inordinate consumption of alcohol or chocolate have been observed) are thought to be celebratory in nature, but further studies are indicated.

- FWs make frequent attempts to discuss their stories with NFWs, rarely with a favorable outcome. NFWs often appear bored, or make some attempt not to look bored. The FW either fails to notice or expresses bewilderment. In extreme cases, an argument ensues and the two separate, usually for a temporary period.

- FWs occasionally seek out the company of other FWs. Perhaps this is because they are so rare, or perhaps they understand each other better than they understand NFWs.

- NFWs apparently are capable of creative thought and retain vestigial memories of early fiction-writing education. Sometimes an NFW will suggest to an FW that the FW write a story around the idea the NFW just had. FWs almost never do this, and instead suggest the NFW write the story. The NFW will almost never do that.

Since FWs produce a unique product that NFWs consume, and since NFWs produce all other products needed by FWs, an economic exchange relationship has developed. The amount of wealth earned by a given FW apparently depends on the popularity and demand for that FW’s stories among the NFWs.

In an economic sense, it is fortunate that FWs are in the minority; otherwise they would have to pay NFWs to read their books, rather than the other way around.

In an economic sense, it is fortunate that FWs are in the minority; otherwise they would have to pay NFWs to read their books, rather than the other way around.

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first significant study of these fascinating morphs and their interactions in the wild. Clearly, the need for more comparative studies is indicated. Confirmation or refutation of the observations made in this analysis is sought by—

Poseidon’s Scribe